A Brief History of Wargames and RPGs

How Fantasy Wargames Became Fantasy Role-Playing Games.

INTRODUCTION

Let’s start with steam engines. As this is the first post on my irregular and personal history and thoughts on RPG’s, let’s start with Charles Fort (1874 – 1932) and steam engines.

Charles Fort was the author of four books on unexplained events, including The Book of the Damned (1919) and Lo! (1931). He was one of the first people to collate and study “anomalous phenomena” and is said to have coined the term “teleportation”, one of the many events he researched, including levitation, spontaneous human combustion, and unidentified flying objects.

My own first reading of Fort was the several references in Louis Pauwels and Jacques Bergiers The Morning of the Magicians (1960), a battered copy of which I clung to and read voraciously during my early teens. In another esoteric connection, it has been suggested that this book partly inspired the works of H. P. Lovecraft – certainly Fort himself inspired The X-Files. The book was also influential on the burgeoning New Age movement in France and England and contains an assortment of odd ideas ranging from alchemy to cryptohistory.

But back to Fort, whom I did not ever read directly, but who I had met courtesy of Pauwels and Bergiers, and then two years later when my esoteric teacher quoted the line in Fort’s Lo! which would stick with me for the rest of my life:

“A tree cannot find out, as it were, how to blossom, until comes blossom-time. A social growth cannot find out the use of steam engines until comes steam-engine time”.[1]

This was presented to me as the abbreviated “When it comes steam-engine time, everyone steam-engines”. A concept I have since seen in practice so many times, both globally and personally – in my case, within the world of tarot cards and esotericism.

Fort’s concept of this ‘theory of submergence’ broke away from the idea of some absolute ‘standard’ for human thought and progress and gave an “organic” model. It suggested that humanity did not progress to some pre-defined order, but rather in the “adjusting constructiveness” to all other living things. As a society, we may have some idea to do something, but unless we have figured out how to smelt ore, for example, the other idea will fall on barren soil. And, conversely, when a thing is possible – most everyone will see it, and some will do it, and some few will succeed at it.

WARGAMING CAMPAIGNS & IDENTIFICATION

Which brings us onto the astonishing emergence of Role-Playing Games, such as Dungeons and Dragons, from the field of wargaming in the comparatively recent early-1970’s.[2] A huge leap, obvious now perhaps in retrospect, yet entirely novel and utterly unpredicted at the time. It was a leap that was resisted at the time, somewhat chaotic (as all creativity tends to be as it must, by definition, upset the established order) and led to energetic power grabs, conflict and betrayal as creators found themselves in a swell of interest beyond their initial intentions.

This story has been covered in recent years by others, most notably and extensively by Jon Peters in three books; Playing at the World (2012), The Elusive Shift (2020) and Game Wizards (2021). The area is also the subject of studies in gaming, such as Storytelling in the Modern Board Game: Narrative Trends from the Late 1960’s to Today (Marco Arnaudo, 2018).

As a keen gamer from my earliest memory, with parents who encouraged games from many family card games, Monopoly, Mousetrap, Cluedo, Mastermind, and so on, I was lucky to grow up almost in parallel to the development of RPG’s. I wasn’t part of Generation 0, but almost certainly Generation 1 of the Role-Playing phenomenon. This is partly why in this blog I would like to record and weave my own experiences throughout a wider discussion of RPG’s.

I also came to wargames very early, through the works of Donald Featherstone (1918 – 2013). One of my earliest memories is my Dad telling me I couldn’t send English Pounds through the post to the USA to buy one of the sets of plastic Revolutionary War Soldiers garishly advertised in one of the Conan, Spiderman or Doctor Strange comics I was avidly buying with my pocket money.

I did eventually end up with a green plastic WWII platoon (barely an “army” as advertised) and that brings me straight to the intersection of a personal story and the universal theme of this post – story-telling, particularly identification and connected narrative.

It is story-telling that is the intrinsic bridge from wargaming to role-playing.

When I played simple wargaming with my younger brother, before we both even learnt chess one summer and were totally obsessed by it, I remember clearly that one of the plastic soldiers was my “favourite”. More so than a favoured marble (mine was a beautiful luminescent sea-green one), this figure – one lying down with a sniper’s rifle on a stand, was personal. In fact, when we played, I would always have him placed on one of the larger sandpiles to take precise aim at any oncoming soldiers without being directly in the field of battle. My brother – who always played the Germans – had a similar favourite, a particularly helmeted field soldier with a canister that was (in his mind) full of water for long marches.

There was a primal identification with these two individual figures for us; they allowed us to enter the game, see it more clearly in our imagination, and – most of all – tell stories, about that time I had managed to shoot one of the commanders from so far away, or he – with canteen in hand – had outflanked us and blown up our supply vehicles.

These stories were not simple, and often connected across many days of games, and were to a lesser extent found in playing Escape from Colditz, where certain wooden coloured pawns would take on a character based on their tactics or movement.

We never found this identification arising in more abstract tokens, such as those in Monopoly for example, where it would simply be a matter of favourites as to playing the hat or the iron, the car or the dog.

Meanwhile, somewhat south of us playing army games in Derby, in Southampton, England, this story-telling within wargames had already been in place for five years or more; it was indeed steam-train-time for connected narratives.

FROM SOUTHAMPTON TO HYBORIA

The wargamer and author Tony Bath (1926 – 2000), first opponent and friend of wargaming legend Donald Featherstone, is widely acknowledged as having one of the first wargame campaign ‘worlds’.

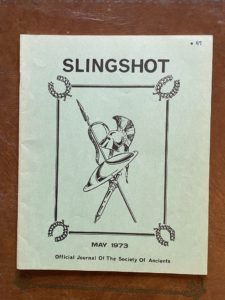

As well as his rules for wargaming becoming one of the prevalent sets, he also founded the Society of Ancients in the same year I was born – 1965. Over the course of several years, he and a friend, Neville Dickinson, developed a dynamic ‘world’ in which many battles and strategies could be conducted. These would have connected narratives, where economic and political impacts would be carried from one game to another, in an overarching campaign.

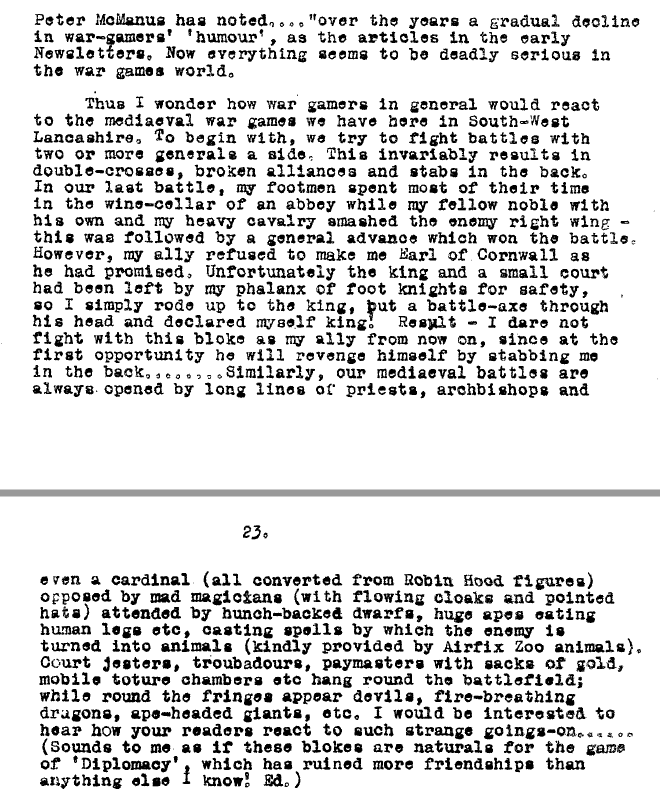

Over time, this world, Hyboria – based on the fantasy world described by author R. E. Howard for his Conan series – would also have rules for weather effects, crop production, diseases and other factors that could impact the wargames being fought across its many countries.

This campaign must have commenced also around 1965, as Dickinson had already developed his own fantasy world for campaigns by May 1967, where he wrote in Slingshot about his mythical continent of CASIA, having decided that many of the existing and “well-known” fantasy worlds had already been taken over by other wargamers. The world of Casia was rather quaintly based on various holiday brochures he had to hand from his wife, so the Isle of Man became Hostigos, and Northern Island became Beshta, etc.

It is most telling that as a footnote to an article in Slingshot magazine, in July 1969, where Tony Bath provided an overview of this campaign world and detailed some of the players involved and their various global machinations between games, Charles Grant (who was now recently editor of Slingshot after Tony Bath), wrote:

“I’ve had more fun out of my twelve months as Prince Vakar of Hyrkania (a greedy, treacherous and disloyal character, as I was informed) than I’ve had from any wargame campaign yet.”

This is one of the earliest statements of the shift – what Jon Peterson calls the “elusive shift” – to role-playing from wargaming that I have seen.

Bath and Dickinson had already (in 1969) realised that it was more fun and manageable to act as “general controllers, umpires and tactical commanders” and feed information to the other players, whilst maintaining a global knowledge of the entire game world and other player choices. In effect, they were pre-dating the concept of “dungeon masters” and “players”.

They also realised that the idea “could only work if the players took a really deep interest in what they were doing…” which indicates the different level of immersion and engagement required when shifting from wargaming en masse in individual battles to a more individualised game experience with narrative connections and consequences across games.

By 1971, players were definitively being given “characters” and portraits of infamous characters being played were a regular occurrence in Slingshot – again, these are amongst the earliest “player characters” in gaming at this time.

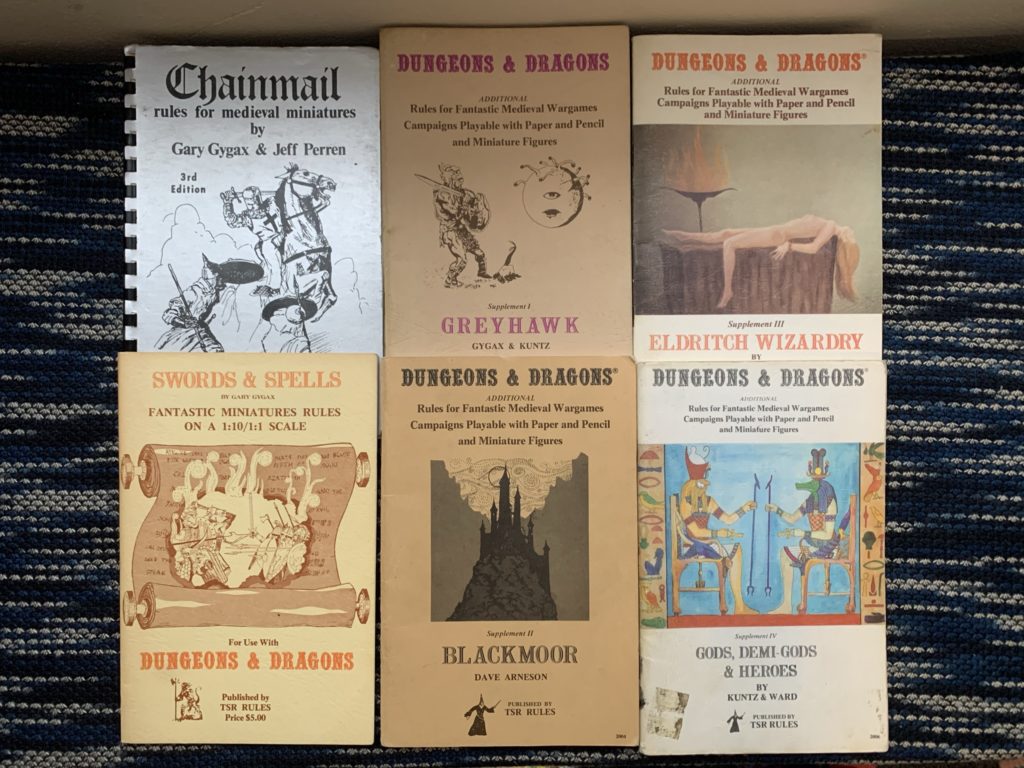

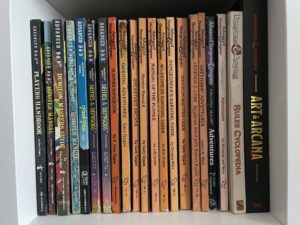

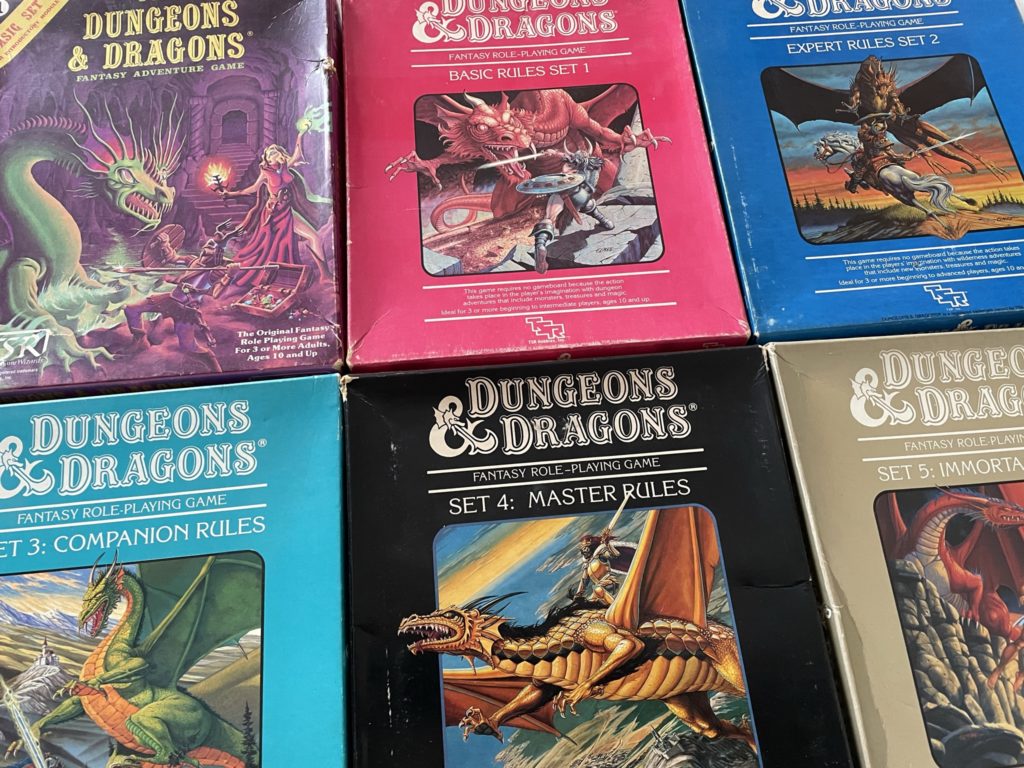

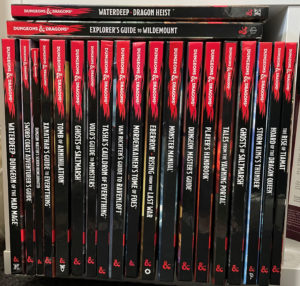

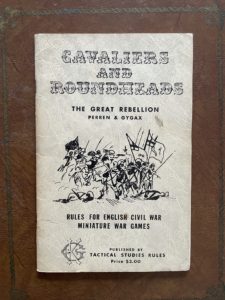

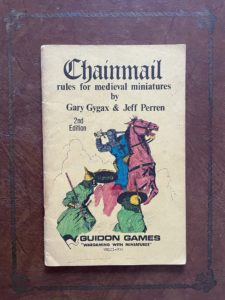

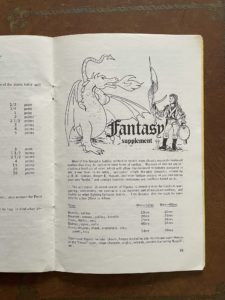

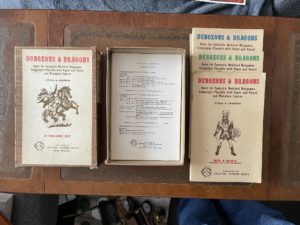

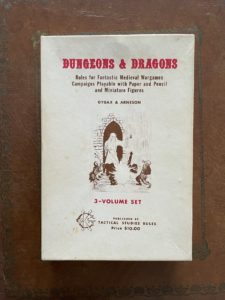

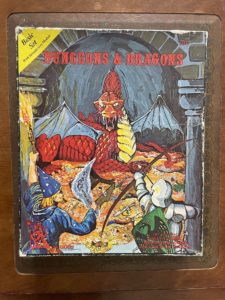

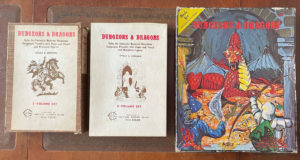

They were now running, with “massive dossiers” the first ‘fantasy campaign’, albeit in a rudimentary way compared to the slightly later but almost immediately parallel development of the same concept in Lake Geneva by Gary Gygax and Dave Arneson, culminating in the fantasy supplement rules in Jeff Perren and Gary Gygax’s Chainmail (1971) and shortly thereafter, the first Dungeons and Dragons game, published in 1974 by Arneson and Gygax.

MEANWHILE IN AMERICA

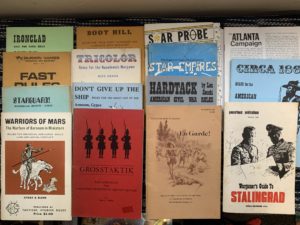

The Twin Cities wargaming groups, a wargaming group at Lake Geneva and others were already experimenting with variant rulesets and Gary Gygax was publishing with an existing small company Guidon and then co-founded TSR (Tactial Studies Rules) with Don Kaye in 1973.

Original Guidon and TSR rulesets including rare Warriors of Mars, withdrawn due to copyright claim by estate of E. R. Burroughs.